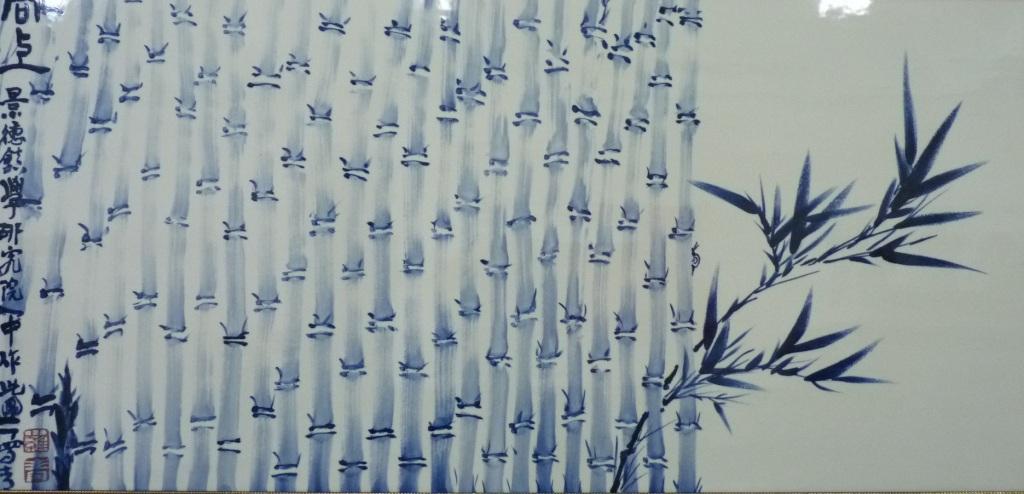

向上 / 羅青陶瓷版畫

“East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” More than a century ago Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), the famous English writer, winner of the Nobel Prize of Literature, asserted his strong belief without any reservation and hesitation. Echoes of the rebutters and defenders ensuing after this controversial remark have also lasted almost one hundred years or so. However, none of the discussant has been aware that the meeting ground of the East and West had already been firmly founded since the 12th century with the exportations of Chinese ceramics to the Middle East and the European countries in great quantity and excellent quality.

Chinese ceramics are not only carriers of daily utilitarian use with various pragmatic purposes but also vehicles of fine arts with high ideas and sophisticated aesthetics. Of all the aspects of the art of ceramics, the graphic pattern brushed on the various ceramic shapes derived their primal inspirations from the combination of ink-color painting and folk art traditions occupying a unique position in the realm of Chinese art had developed and acquired its own subjects, themes, techniques and aesthetic principles through the periods of Tang and Sung Dynasties and culminated its performances in the Yuan, Ming and finally reached its zenith in the Qing Dynasty.

The features of the painted Chinese ceramic patterns could be observed and described with followings three aspects:

The first feature is of what I called the Cycling Mode of Thought adopted by the ceramic painters which can be traced back to the primeval times with the appearance of Neolithic potteries. As we know that the patterns executed on the ceramic shape which is often a round one can begin at any point as the artist chooses. Nevertheless, after the patterns are completed, the beginning and the end will join each other into one and consequently make both the starting and ending points vanish into a harmonious whole. Due to this particular ceramic painting characteristic, a new aesthetic principle shared by both graphic construction and verbal structure followed by artists, writers and poets was born in the 6th century and culminated in the 13th century.It is named “Qi起、Cheng承、Zhuan轉、He合” that can be roughly translated as “Rising, echoing, turning, uniting ”.

The second one is of the Temperature Mode of Thought. The pattern painted in glaze on the ceramics must be fired and crystallized at high temperature whose slightest change of degree will result in very different final effects to the designated painted pattern.

The temperature also will bring accidental effect to the glazed painting with a surprisingly autonomous extemporization. This unique feature and concern of the ceramic artists are by all means beyond that of the painters of canvas and paper.

The third one is of the Participation of the Viewer. Once the painted ceramic has been completed and displayed, the viewer and displayer will have to decide which side or from what point of view and what angular field the designated work of art should be confronted or displayed. Of course, the round shape ceramic can also be shown on a carrousel plate with an ever changing view of 360 degrees. In the mean time, a finished ceramic product could invite its viewers of all ages to inscribe anything they like with markers which can be easily erased in no time.

In the past one hundred and sixty years, since the Opium war of 1840, Chinese society has been moving from an agrarian one to an industrial one, and in the recent two decades, at a dazzling speed, marching toward a post-industrial condition. Chinese civilization has undergone more or less the similar trends correspondingly and has demonstrated a miraculous adaptability in the vicissitude of internal political reformations and revolutions and the turmoil of foreign military invasions and commercial erosions.

Chinese ceramic painting as one of the most poignant art forms in Chinese civilization has witnessed and recorded these cultural changes and intellectual transformations with many a great artist and artistic performances.

The main feature of the ceramic artists of the twentieth century are as follows:

(1) A brand new weltanschauung, a novel worldview, which is completely different from that of the artists of the nineteenth century, has been born. A scientific solar system and a more comprehensive global view substitute for the sino-centric conception and the ancient mythological world.

(2) Geographically, Chinese artists have been moving continuously toward southern part of China , from the Yellow River region to Yangtse River area, to the Chiangnan region of China, and then to the big cities along the coastal line. And finally, after1949, an unprecedented great number of intellectuals migrated to the semitropical island, Taiwan, which is situated outside of China proper. For the first time, there is a place that allows Chinese intellectual to investigate and re-examine Chinese culture outside of China proper, offering an oceanic view to interpret Chinese civilization past and present from an insular angle, with the vast pacific deep as a background. In the mean time, both political China and cultural China have been divided too. As for political China, there is one on Mainland China following communism and socialism, another on Taiwan advocating democracy. As for cultural China, two laboratories have been established, one is of continental orientation in mainland, another of oceanic orientation in Taiwan.

(3) The “Traditional China” or the “Agrarian China” has been smashed by the invading industrial society from the West in the late 19th century and broken into pieces like racked mirror whose dismembered parts were scattered not only in China proper, but following the footsteps of overseas Chinese, traveled and disseminated into many a Western country in various diasporas all over the world. Chinese ceramic artists, with new subjects corresponding with new techniques have traveled into countries East and West around the world. A new China or rather many new “Chinas” were born in these broken mirrors, especially after World War II. They appeared in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore as well as in the big cities of the West Europe and the North America. And more recently, they emerged miraculously in Canton and Shanghai areas as well. Images and insights of Chinese artists and Chinese culture reflected in these broken pieces of mirrors are both relevant and irrelevant, are at once united and independent.

Multiple approaches of aesthetics and techniques have been adopted by the artists in their paintings to show the varieties of historical phases experienced by the Chinese people both in Mainland China and around the world.

There is pastoral lyricism incorporated with urban modernism, cynicism blended with good humor, and criticism and satire fused with universal love and understanding. The graphic language in the paintings is mixed with the verbal language of poetry executed in fine calligraphy performed in the form of inscriptions. The two are integrated with new aesthetics shown in rearranged compositions with a symphony of leaner movements intertwined with a carnival of colors.

These ceramic paintings are traditional and modern or postmodern at once. Just like what China has experienced in the past 60 years, a marvelous combination of societies of agriculture, industry and post-industry moves side by side braving the turmoil and vicissitude of different national and international climates.